Why don't Jews write horror stories?

An interview with Jeremy Dauber, historian of American horror (and Yiddish literature).

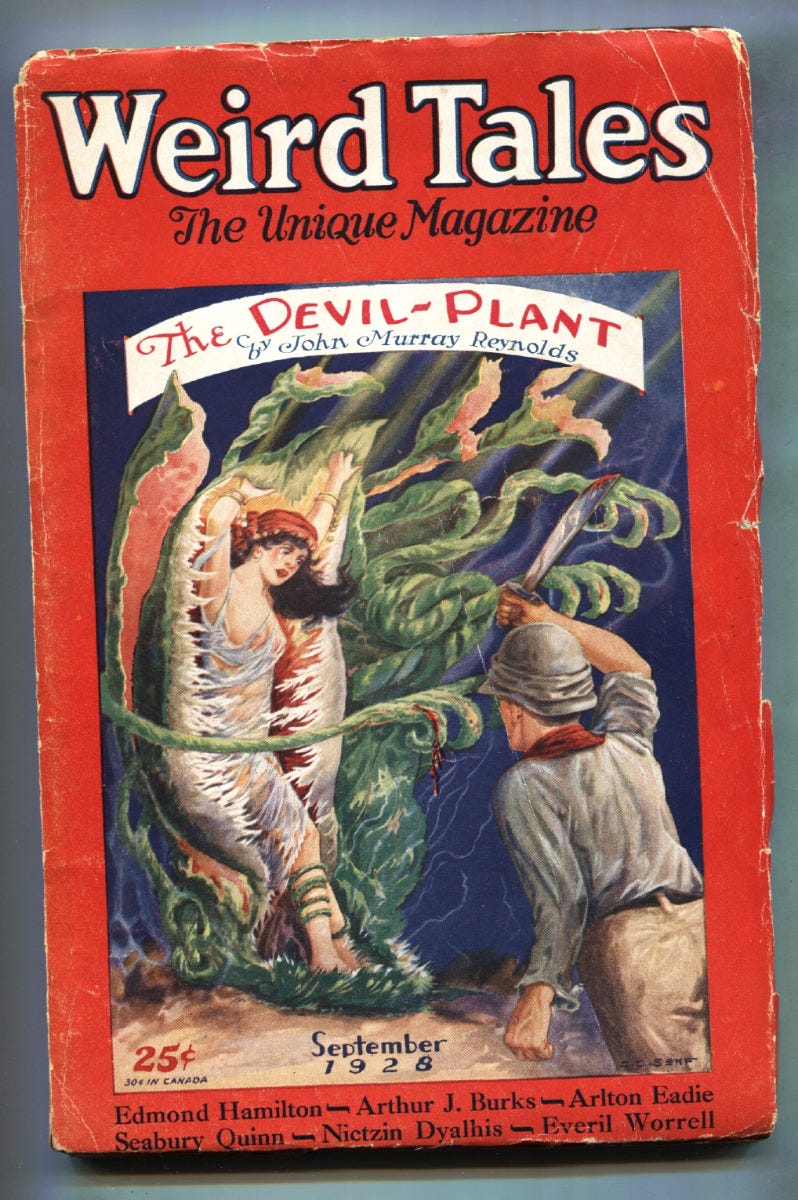

Americans love horror stories. This point was recently driven home to me by Paperbacks from Hell, a history of American pulp horror.

For Grady Hendrix, the book’s author, American horror stories are so numerous and varied because Americans have secret anxieties about basically everything. You can write stories about devils, sure, but you can also write about domestic animals, your body, the earth, houses, television. Already-scary things can be zhuzhed into scarier forms and underlying concerns about mundane reality can concretized. A ghoul can haunt your family—or your family can turn out to be ghouls.

None of this is news. Horror stories have always been full of subtext, if you’re looking for it, and the people who write the stuff are usually quite aware of what frightens people.

The more I read about horror, though, the more I come back to a question: why is this not a major Jewish genre?

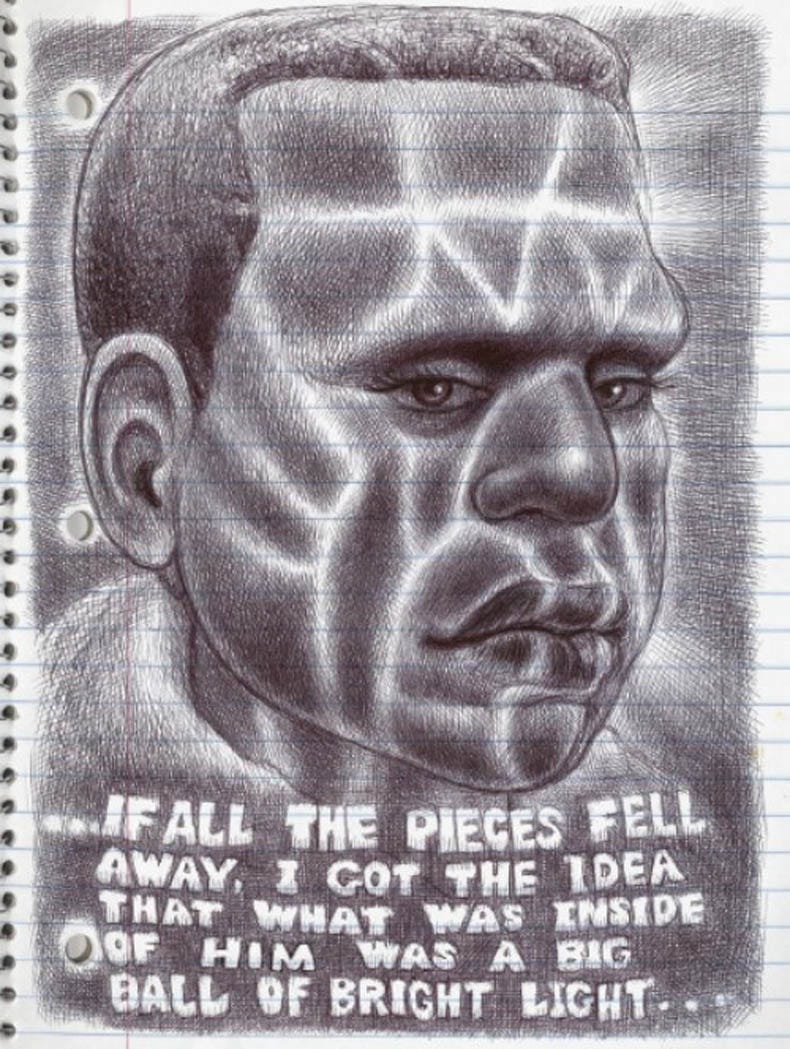

I ask this in particular in light of My Favorite Thing is Monsters, Emil Ferris’s magnificent graphic novel about a young girl obsessed with horror. The reason for her obsession, the book quickly reveals, is that it protects her from the horrors of her life. A mother dying of cancer is too much to withstand; it’s easier to pretend to be a monster. Some texts need to be subtexts.

Why don’t we do that? Why don’t we regularly enter the realm of the fantastical to process trauma and pain? I don’t know, but we largely don’t. We definitely talk about the Holocaust and other Jewish tragedies, but even our fictionalized accounts don’t stray far from actual events. (Israeli filmmakers also didn’t do horror until very recently.)

Is it because the pain is too great? This seems unlikely. Historical tragedy certainly inspires good horror; Jordan Peele and other black horror creators demonstrate this regularly. Why not the Holocaust? Why not the Crusades? Why are we so uninterested in telling each other scary stories?

To answer these questions, I wanted to talk with Jeremy Dauber. Dauber’s newest book, American Scary, tells the story of horror writing (and filmmaking) in America over the last 400 years.

Jews are conspicuously absent from Dauber’s book—which wouldn’t be notable, except Dauber is a professor of Yiddish at Columbia University. That makes this a strange interview, since basically all of my questions are about things that the book doesn’t cover.

I don’t think Jeremy and I got to a clear answer, but I left the conversation feeling more convinced that the problem is actually quite important, that it’s a backdoor into Jewish trauma that has the ability to generate new insight. I don’t quite have all the answers yet, but check out this space in a year—and check it out later this week for a great piece of Jewish horror fiction, an Exception That Proves The Rule!

Here’s my conversation with Jeremy Dauber.

David Zvi Kalman

Let's just jump in. Do Jews have horror?

Jeremy Dauber

Everybody has horror. Almost every culture grapples with its fears in both real life and fictional contexts, and sometimes those lines are a little blurred. So there is absolutely Jewish horror, horror that involves Jews, horror that takes particular traditions and inflects them in Jewish ways and is inspired by Jewish history, culture, theology.

David Zvi Kalman

Why do you think it hasn't crystallized into a genre in the way that American horror has? Your new book starts with the Salem witch trials, and you provide this extensive pre-history of the horror genre. For the Jewish tradition there are certainly similar horror precursors: curses in the Bible, dybbuk stories, Jeremiah's prophecies. Why do you think those things didn't develop into a Jewish horror genre in the same way?

Jeremy Dauber

So let's step back for a second. It's absolutely the case that stories that we would consider within the conventional genre of horror are omnipresent in Yiddish literature. Dybbuk stories, stories of demons, folk and fairy tales, elves, and synagogues of the dead—it's just full of them. In fact, you could make a significant argument that Yiddish literature is suffused with a literature of fear, which is different from the genre of horror.

I point out in the book that [horror] is narrowly defined as a kind of convention and sort of marketing thing. It's not clear that Nathaniel Hawthorne or Edith Wharton or Henry James would have thought of themselves as horror writers in the sense that we think about it now, or that their readers would have thought of themselves as reading horror. In the 19th century some would have said, this is a ghost story.

The real question I think that you're asking is why aren't Jews represented in the horror section. I think that there's two reasons, and they're connected.

One reason is that much of the Jewish presence in American mass culture in the 20th and into the 21st century has been one about sort of trying to have the maximal popular appeal. So some of our greatest Jewish horror auteurs of America in the 20th century, someone like Ira Levin, who writes Rosemary's Baby, is saying, I'm going to write something that's really going to prey on the anxieties and the fears of this general audience. The same with Steven Spielberg. Jaws, I think it is fair to say, is not really a Jewish horror movie.

So that's part of it. That ties into what we might call an ideological explanation. If a lot of horror is about haunting—about the shadow of the past onto the present—then one of the things that American Jewry (and I'm simplifying outrageously here) is interested in doing is not looking at the past, but looking forward to a bright future. As a result, those claims that many kinds of horror have, are almost the opposite of what American Jewry wants to do in its dream life. They don't actually dig in in exactly that way—again, ceteris paribus.

That combination leads to what I agree with you is the surprising finding that as omnipresent as Jews are in so many aspects of American mass culture, they really are underrepresented in a surprising way in these foundational narratives of American mass culture.

David Zvi Kalman

I have a hard time imagining that the Jewish soul is internally some bright and sunny thing.

Jeremy Dauber

The other side of this is that horror is very faithful to its genealogies [i.e. ghosts, vampires, etc.], and a good chunk of the American Jewish community involved in mass culture was either not interested in those past traditions or didn't know them. I think that the last twenty or thirty years have seen increasing tendrils towards Jewish horror, both in having more knowledgeable voices and in a re-engagement with the identitarian roots of this particular aspect of their tradition. [The internet also allows people to find] an audience that can be smaller than ever before, while still being a meaningful audience that provides [financial] return.

David Zvi Kalman

Do you think that the violence of Jewish history actually makes it hard to create straight horror stories about violence, especially body horror? Recently I was reading the medieval Jewish chronicles of the Crusader massacres and they bear more than a passing resemblance to accounts of October 7th in their descriptions of home invasion, parents trying to shield their children, all the rest.

Is the reality of Jewish history too awful to maintain horror in the same way?

Jeremy Dauber

One thing that we haven't really talked about is the huge appeal of holocaust related literature. It is, if not omnipresent, then certainly very robustly present in the contemporary marketplace.

There's also lot of work that we don't normally put into the horror category. Bernard Malamud's The Fixer, about the blood libel against Mendel Beilis. It won both the Pulitzer and the National Book Award. Nobel Prize winner Isaac Bashevis Singer, who was an immigrant to America and lived most of his life in the United States, writes more conventional horrors. Saul Bellow’s 1947 novel, The Victim, is a story about antisemitism. We don't think about these as horror stories, but it's present.

David Zvi Kalman

But I want to press you on this because I think that there is a big difference between fictionalized accounts of real events and stories that are clearly not intended to be real. And if I understand, one of the things that horror does as a genre is that it allows people to project fears that are too dangerous or too scary for real life onto fictional worlds. So I have a hard time understanding fictionalized accounts of real events as being the Jewish equivalent of horror.

Can I put forward a suggestion?

Jeremy Dauber

Yeah, please.

David Zvi Kalman

I think one of the difficulties that Jews have with the horror genre is that the deepest, darkest Jewish fear is not death.

Jews have died in all kinds of situations, and in part because of that there's a Jewish mythos of persecution and survival, and so the fear of destruction is not the deepest concern.

I think the deepest fear might be something different. Perhaps something about being forgotten: by the world, by God, or being superseded or being misrepresented. The idea that Christians or Muslims or other groups were right about us. It’s not a fear of genocide, but a fear of rotting from within. I see those concerns show up in a lot of online dialogue.

I’m curious what you think about that.

Jeremy Dauber

In many ways I agree with you. In previous books, I've talked about this as the greatest and darkest Jewish joke of all time: they call us the chosen people, but what if we're wrong? Is this what being chosen looks like?

In my book on Jewish comedy I argue that in some ways this animates the book of Esther, a book where God's name isn't mentioned. The book’s leading metaphor is coincidence, is lottery. What if all this salvation really is just chance? So one interesting way of thinking about this is that the Jewish sensibility has taken that fear and put it into laughter.

In the American context, I think, one of the greatest—one of the scariest—American Jewish novels is Philip Roth's The Plot Against America, which was published a few years into the 21st century. I think it strikes at a contemporary American version of this myth. What Roth suggests in the book is the possibility that “it” could happen here. In the end—and I apologize for spoiling this generation-old novel—as I read it, Roth basically doubles down on America; this is a bad patch, but “it” really can't happen here. Contemporary events might have made Roth write a different ending to that novel, or maybe it would have had a different reception.

But I think the overwhelming majority of American Jews—their deepest and most cherished aspects of Judaism are not at heart necessarily theological; they’re communitarian, they’re sociological, they’re whatever they are. It's not about, “did God choose us for.”

So dybbuk tales, for example, in some sense come out of an anxiety about a challenge to the theological metaphysical order. Is there an immortal soul? Well, a possession of a dead spirit shows that there is an immortal soul because otherwise, how would the spirit be there? I don't think that is an animating concern, uh, for a lot of people these days, certainly not for a lot of American Jews.

David Zvi Kalman

Where do you think American Jewish horror is going next?

Jeremy Dauber

There is undercurrent—maybe becoming just a current—that the promise of America for Jews is under threat. Whether or not this is going to be the beginning of something that goes much further, I think that could become a very generative source for horror in the American Jewish community.

As a Jewish educator, this is very meaningful to me. There are more people turning towards learning more about Jewish history and culture, which I think has been one the few silver linings (for lack of a better phrase) of this horrible recent period, which might result in the kind of deeper knowledge that might say, hey, I can figure out with my creativity, something to play with in this way that will work in an American context. That would be very interesting to see.

I'm Jewish and I write horror. So do many jews.

https://open.substack.com/pub/marlowe1/p/hey-man-by-tim-lieder-fiction-extra?r=sllf3&utm_campaign=post&utm_medium=web&showWelcomeOnShare=false