If I had to pick a single piece of media to describe Torah in the 21st century, it would be Megilat Ḥam-ed, a truly mind-bending achievement of scholarship and parody produced just a couple of years ago.

What is Megilat Ḥam-ed, you ask? Well, it’s quite simple. There’s a cartoon called the Simpsons that has a well-regarded scene called steamed hams. This is a retelling of that scene—but it’s in Biblical Hebrew, and it’s chanted as though it were the Book of Esther.

Why the Book of Esther? Because that’s the book you read on the holiday of Purim and this is an example of Purim Torah, an ancient form of Jewish writing that is more alive than ever. The genre, which you can read about in Danya Ruttenberg’s excellent post from this week, is all about Jews making fun of their own literature for Purim, a holiday that is all about comedic reversals and more than a little about drinking. So, for example, you might get a medieval Talmudic “treatise” that’s about how it’s forbidden to drink water on Purim (it’s not) because you should be getting drunk.

Purim Torah is a kind of parody, a type of humor that is entirely premised on the gap between form and content: We think Spaceballs is funny because that’s not how Star Wars actors are supposed to behave. What makes Purim Torah special is that the parody is being produced by the same people who produce the real thing. This means that when rabbis parody themselves they are doing something hugely important: they are acknowledging that it is possible to take bullshit and put it into the form of sacred writing. They are telegraphing that they understand the power of sacred styles. They are winking at us.

I think about this a lot these days. Contemporary culture loves parody; it is the stuff of memes, it is the air that we breath. The gap between style and substance is so much assumed that we rarely think about it. Making good parody today is actually quite difficult because we expect that any idea can be poured into any mold.

(This isn’t just a story about technology, but technology is a piece of it. Computers are good at translation, and AIs are great at it. As I have written before, the cost of translation is now approaching zero, which means that we have more choice than ever about how we wish to imbibe ideas. The relationship between form and substance is faltering.)

For the most part this is great—but when it comes to religious ideas it presents a problem. Purim Torah tells us that sacredness has always been connected to style. If style is infinitely malleable, where does sacredness go? Does it just evaporate?

Sacred style is an endangered species

The answer, to a degree, is yes. The world of parody in which we live is quickly eroding the source material that gives it life. We rarely confer reverence on any style—and we are especially hesitant to let style alone dictate norms of behavior. Sure, we can do things to slow the erosion, but the writing’s on the wall: time is running out for sacred styles.

But the world does not need sacred styles. We can live our lives—even religious lives, sacred lives—without them. Belief in a robust Jewish future means believing that there is meaning beyond rabbinic genres, beyond Hebrew, beyond even text itself. Where we once gave deference to form, we must now defer to substance. Perhaps the idea of sacred styles was only ever a training concept, something that allowed us to think about authority earlier in our history. Perhaps it is time to move from “how did you say it?” to “what are you saying?”

In the messianic era, remarked Maimonides, most of the Bible will be nullified, but the Book of Esther will remain. I don’t think we’re quite at the messianic era, but Purim Torah has certainly escaped the bounds of its holiday. The modern era seems hell-bent on allowing Torah to exist in any place, in any format. Perhaps we should let it.

Or maybe this is all just Purim Torah.

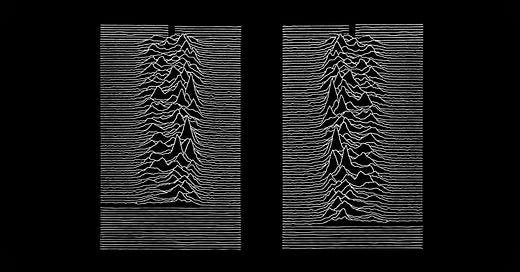

P.S. As I was writing this, Isaac Mayer—the creator of Megilat Ḥam-ed—published a new video. Appropriately, it uses AI artwork.

I'm glad you like my work! The AI art I used was two years ago, when it seemed more like a trippy, weird novelty than the threat to actual artists' careers that it ended up being. I won't use it again. Anyway, today I'll be posting my megillah for this year

I believe Purim Torah is funny for the same reason Conan O'Brien's shows were: "Someone wasted a lot of brain on *this*?!"