Did Torah miss the boat on mobile apps?

Christian Bible apps are amazing. Did we fall behind? Are we on a different path?

Pornography is consistently one of the first kinds of content to show up on any new digital platform. You may already be aware of this. You might not know that religion is typically close behind.

The chief reason is that organized religions like to spread their ideas, so they tend to be highly interested in new methods of transmission. Whereas pornography spreads quickly because there is always huge demand, religion spreads quickly because there is always huge supply—meaning, there are always religious people who want their ideas out in the world. (I wrote about these strange bedfellows in one of the earliest posts on this site.)1

For more than seven decades, religious leaders and religious programmers have worked together to create a cascading series of bespoke technologies that have radically transformed the way that religious texts are studied and made available.

If you’re involved in Jewish education, you probably know part of this story. You may have used Sefaria, or visited chabad.org. If you’re an expert user you may have spent time with the Bar Ilan Responsa Project or hebrewbooks.org or Otzar HaHochma or even the Genizah Project.

Tools like these tend to be very well known inside religious communities and totally unknown on the outside. Because of this, you may not know that Christians and Muslims have been developing very similar tools at more or less the same pace.

These tools all looked very much alike, but this is changing. The rise of cheaper and smaller computers has created a lot more freedom to shape how followers interact with sacred texts, and different religious traditions are increasingly following different paths.

Crucially, not all of these pathways are equally successful—and there’s no guarantee that Jewish wisdom will continue to succeed in the digital platforms of the future. In fact, there are troubling signs that digital Judaism may be stalled, despite its wealth of prior successes.

From mainframes to mobile

In his book People of the Screen, the scholar and programmer John Dyer argues that the digital Christian Bible has been through four stages of development (if you subscribe to Belief in the Future you’ll hear my interview with him later this week). Here’s my summary:

Pre-consumer era (1950s–1970s). The first electronic Bible was created on a mainframe in 1952. The first application—a concordance—was developed in 1957. These tools were off limits to almost everyone both because most people didn’t have computers and because the applications only benefited Bible scholars.

Desktop era (1980s–early 1990s). Commercial Bible software began appearing almost as soon as personal computers came to market. The Word Processor (great name!) was released for the Apple IIe in 1982. Users were largely sermon-givers and other people who consulted the Bible professionally. The tools became more sophisticated over this decade, and the introduction of the CD-ROM in the late 80s dramatically increased the size of digital religious libraries.

Internet era (mid-1990s–early 2000s). The Bible appeared online almost immediately after the creation of the modern internet. For early users a key benefit was the ability to consult multiple translations with great ease.

Mobile era (late 2000s–today). Bible software had been developed for many mobile devices—including the failed Apple Newton—but it was the launch of the iPhone that really kicked off the Bible app economy.

The Jewish version of this story looks very similar, but there are a few key differences:

Smaller marketplace. Predictably, there just weren’t as many people involved in digitizing Torah; a few people and organizations dominate the story. Given the sophistication of the software, this makes their accomplishments all the more impressive!

Larger dataset. Early Christian digitization was driven by a desire to see the Bible from every angle: every instance of every word, every useful translation, every lexicographical note. For Jewish digitizers, on the other hand, computers offered the tantalizing possibility that the vast canon—which includes the Bible, two entire Talmuds, and thousands of commentaries, codes, and responsa—was simply too large for even the most learned of scholars to completely master. Jewish digitization wasn’t just about convenience or ease of access; it was about improving Torah study past the hard limits of human memory.

Catering to the “pro-sumer.” Christian developers were often evangelicals who wanted the Bible in as many hands as possible, and so the software moved steadily from academic power-users to preachers to the public. Jewish software, on the other hand, was about accessibility but not necessarily appeal; the software was great at giving you Torah, but your motivation to learn Torah in the first place typically had to come from some offline source. Because Jewish developers assumed a certain level of interest, the line between “professional” and “casual” use is much blurrier in Jewish products. It wasn’t just rabbis and academics who wanted tools to navigate the vast canon; highly knowledgeable day-school and yeshiva graduates were just as capable of using those same tools. This has led digital Torah tools to take a “professional consumer” approach, with sites like Sefaria anticipating that the user will probably want to examine many interlinked texts in a single session (PC-era consumer software, like DavkaWriter, also boasted about the size of their collections). This has also meant that digital Torah has not always been so accessible to true novices, a point which we’ll re-examine below.

In short: Jewish and Christian consumer markets look quite different. As Bible/Torah software has become more consumer-oriented, the apps have increasingly diverged.

What does this look like in practice? Because readers of this column are more familiar with Jewish software, I’m going to focus on Christian apps. Let’s take a look at one of the most popular: YouVersion.

Duolingo, but for Jesus

YouVersion (a.k.a. The Bible App) launched shortly after the iPhone itself. If you’re in New York you may have seen its stylish subway advertising:

Now, you might think that something called The Bible App is just that: an easy way to look up Bible passages. Like Kindle, but with one free book pre-installed and no option to download any more.

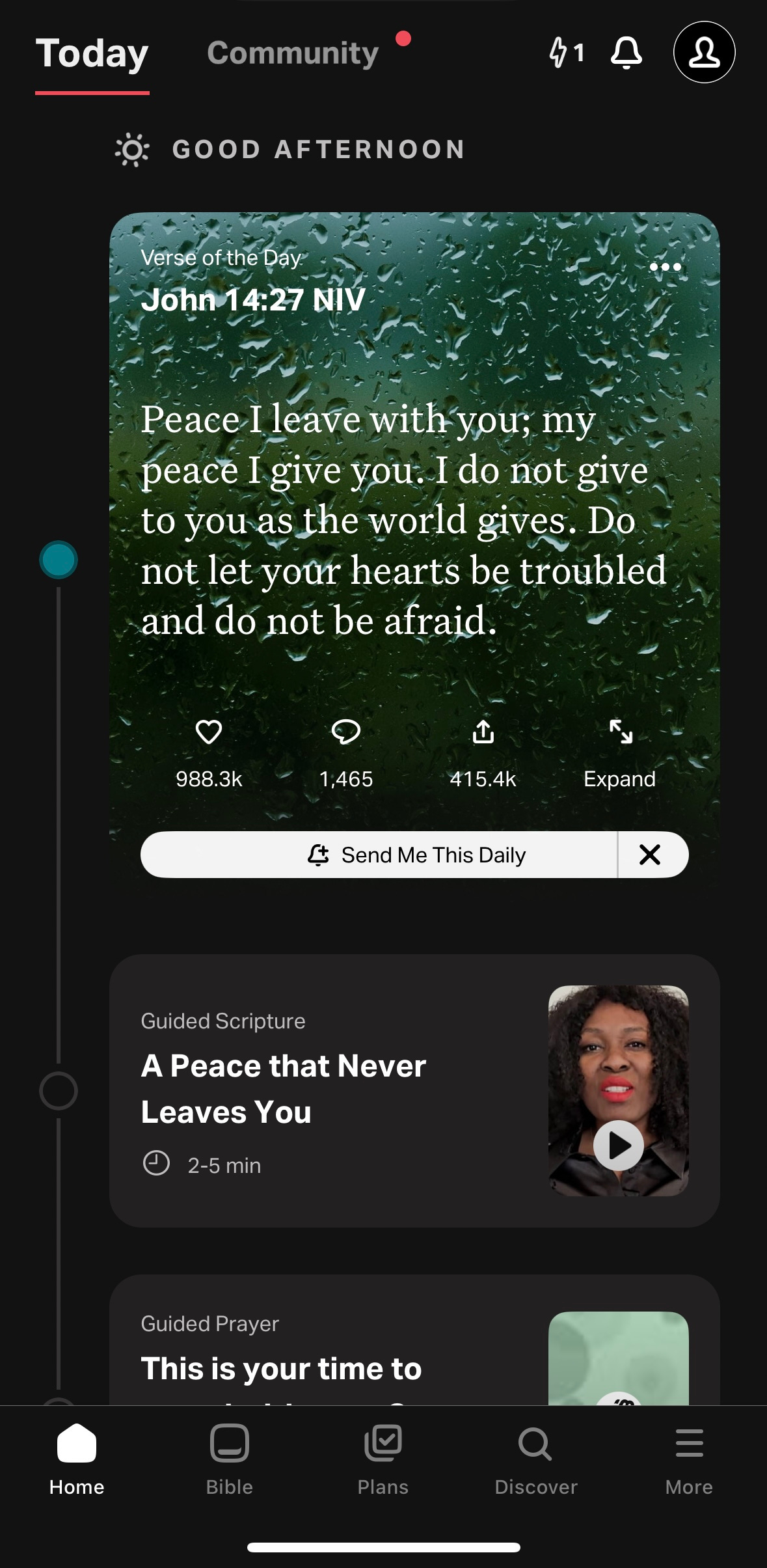

Oh, my sweet summer child. It’s not that at all. When you open the app, this is what you see.

You’ll notice that, yes, you can access the Bible at the bottom, but that’s not the default engagement option. Instead, you are shown a single verse, and that verse very notably:

is inspirational in a self-help sort of way;

requires zero background knowledge of the Bible;

doesn’t assume you believe in Jesus.

The rest of the content on the page builds on this verse in a way that is familiar to any social media user. You can like, share, and subscribe for more Bible verses. You can watch a short video where someone expands on what the verse means. You can read some questions that prompt you to consider how the verse’s wisdom applies for your own life. You can participate in a guided meditation, or recite a prayer supplied by the app.

In other words: the app isn’t just showing you the Bible. It’s selling you the Bible. And it’s doing a damn good job.

More than that: it’s trying to sell you on Bible study as a daily practice. Once you’ve clicked through all the content, you get a small reward: a checkmark that tells you your Bible reading practice has reached its 1-day milestone. You’ve just started a streak, and now you have to keep it up!

This idea of regular practice is constantly reinforced. The “Plans” tab offers dozens of courses of study based on what your personal struggles (Anxiety / Peace / Loss / Jealousy / Temptation / Joy) or interest in specific books of the Bible. Some plans are for men, or parents, or youth, or beginners. You can follow particular teachers, too.

And, of course, there’s a social aspect. You can connect to friends using the app. You can share out basically any content you see. And if you share your location the app will tell you about churches in your area.

In sum: every mobile engagement technique that you’ve ever seen is somewhere in this app. It’s gamified. It’s socialized. It’s addictive by design. It’s very good at what it does. (And I don’t even have space here to talk about Hallow and the universe of Christian meditation apps…)

Duolingo, but for…Torah?

Notably, YouVersion didn’t start out looking anything like this. In its first incarnation the app’s main value-add was crowdsourced annotations—sort of like genius.com, but for Bible instead of rap lyrics. But this model didn’t have much success, so its developers—who are funded by private philanthropy, including Hobby Lobby founder David Green—learned a thing or two from the growing playbook of engagement techniques that are heavily employed by TikTok, Duolingo, and virtually every other top-100 app (as I’m writing this, YouVersion is the 58th most downloaded free iOS app).

There are no Torah apps like this. The question is why.

The proximal answer is very clear: no Jews, not even Chabad, not even Aish HaTorah, care as much about selling the Bible as evangelical Christians. YouVersion is just the latest in a centuries-long process of trying every possible technique for making the Bible an appealing text. That process doesn’t really care where users start, as long as they end up with Jesus in their hearts.

Some Jewish groups do care about outreach, but that outreach almost never starts with a Jewish text. Instead, the attraction is typically community, communal practice, and Zionism: Shabbat candles, meals, tefillin, trips to Israel, matzah, books for children. Jewish texts are not the entry point.

But this begs the question. Why not? There’s even a famous Talmudic text that praises precisely this sort of absurd distillation!

There was an incident involving a gentile who came before the sage Shammai.

The gentile said to Shammai, “I want you to convert me to Judaism on condition that you teach me the entire Torah while I am standing on one foot.”

Shammai pushed him away with the builder’s cubit in his hand.

The same gentile came before the sage Hillel. He converted him and said to him, “That which is hateful to you do not do to another; that is the entire Torah, and the rest is its interpretation. Go study.”

See? It works! Why not make a YouVersion (call it “1Foot” or something) filled with inspiring quotes like that?

You can’t actually learn the Bible one verse at a time

One answer is that it doesn’t actually work. YouVersion may sell you the Bible one verse at a time—but a person who studies this way is going to have a profoundly different understanding of what the Bible actually is.

John Dyer has fascinating evidence to back this up:

The data suggest that Bible readers tend to see a kinder, gentler God when they read about him on a screen and yet they report feeling more discouraged and confused by the encounter. Conversely, print readers tend to emphasize more of God’s holiness and judgment, but report feeling more fulfilled and encouraged by the encounter.

This is wild! If you TikTok-ify the Bible, people will have TikTok-like feelings about it. They’ll get quick hits of inspiration, but they’ll miss the bigger context, and they may walk away feeling empty. You can only learn Torah on one foot for so long before you fall over.

To this you could easily retort: so what? Even imperfect tools are powerful. There are plenty of milquetoast and kitschy entry points into Judaism. With so much potential upside, why not try this one, too?

I think the answer lies elsewhere, and it gets to something very deep about what Jews understand Torah study to be.

“Stop crying and fight your Father”

You may be aware that there’s a Seinfeld episode called “The Strike” which invented a holiday called Festivus. George, the son of the inventor, hates the holiday. You don’t need to know why; the last twenty seconds of the episode say it all.

There’s something about the immortal line stop crying and fight your father that reminds me of Jewish learning.

Learning to study Torah isn’t always about learning to love the Torah; a lot of the time you’re actually learning to fight the Torah, to attune yourself to everything that is troubling about it—whether that’s logic, syntax, or values—and take ownership by vanquishing it. The Passover Seder actually mandates that adults do strange things during the meal just so the children ask why their parents are being weird. That’s a very different way of getting engagement than “check out this beautiful verse!”2

Now, you certainly can be inspired by Torah. You can fall in love with it. Ilana Kurshan’s memoir of Talmud study will tell you that story. But it’s not a simple love, and distilling it to a single verse is basically impossible. There’s no meet-cute moment for Talmud.

If engagement means battle, your app isn’t going to look like YouVersion; it’s going to look like Facebook—and indeed, Jews have been arguing about Torah on the internet since the internet has existed.

More than that: Torah love is also about getting lost, about feeling small in the face of a vast and ancient wisdom. Sefaria’s beauty doesn’t come from any one text, but from the sheer multitude of texts at your fingertips. It’s giving Belle in the library.

At least, that’s why everyone I know likes Torah. But then again, I’m friends with a lot of people with PhDs in Jewish studies. Is there space for a YouVersion for normal Jews (or the Jewish-adjacent)? Should we tell people that one pathway into Judaism is simply to love Torah because it has ideas that speak to their lives?

Try this one weird Talmudic trick

I think the answer is yes—but building an app like that is emotionally fraught and lots of people embedded in Torah study are going to hate it. (It doesn’t help that some high profile attempts to frame Torah this way are problematic.) When you’re at that level it’s very hard to remember just how little newcomers know or care.

Many people who study Torah at an advanced level didn’t have an aha moment when they fell in love. Instead, they were forced to go through years of text study and accidentally found their love along the way. That’s a reasonable model—lots of education is like this—but it doesn’t need to be the only one. Jewish texts contain plenty of straightforward wisdom; it just usually isn’t isolated out into quick hits of inspiration.

But I think it could, and I think it should. Torah’s intertextuality plays well for intellectualizers, but people who are more heart than head often struggle. Not everyone needs to fight the Torah; sometimes it’s OK to just enjoy things. Mobile platforms are optimized for a certain type of engagement, and they should be used to the fullest. If that means that you end up with people who relate to Torah in a totally new way—well, this isn’t the first time information technology has changed the way people study Torah.

What a Jewish version of YouVersion would actually look like

That being said, I think we could do things a little differently.

First, it matters that Torah is the wisdom of a particular people. Yes, there is universal wisdom, but it also emerges out of the experiences of a specific identity. A lot of Jews want to learn Torah to understand themselves; apps should reflect that dual purpose.

Second, the learning trajectory might start with inspiration, but it should move people towards dialectic study. You ultimately want people to feel like the texts are for them to own. I’ll admit that I don’t quite know how to do this, but I don’t think it’s an unsolvable problem.

Third, it can lean into mystery. Some of the most interesting Jewish texts are exciting because it’s not entirely clear what they mean. These ambiguities create an opening for the airing of disagreements, modeling for users that they play a role in the development of text study.

Fourth, it should laugh at itself. For lots of young people, being overly serious is a sign of fakery. Vulnerability is actually a benefit, and so is imperfection. The Torah can be both. There’s no reason not to show that.

Lastly, the wisdom of the tradition needs to be interwoven with ritual practice and offline practice. A lot of it just doesn’t make sense without those references. Some of this you can do in the app—teaching people how to do a mini Shabbat, or a guided Jewish meditation—but it should also direct people towards local resources, too. Unlike apps that wish you’d never leave, this style of Torah app should clue people into when they need to put down the phone. Given that chucking the phone into the river isn’t an option in modern society, this is the next best thing.

For the sake of a single verse

If you’re not convinced that this is a good direction, let me make one more pitch.

A big part of the resistance to gamified, mobile-first Torah apps is that they drop intertextuality for the sake of an immediate dopamine hit. You read verses out of context and are thus not truly part of tradition.

But if Torah is an ongoing project, is it really possible to read verses out of context? Isn’t every verse in conversation with the life of the person reading it? Isn’t that why wisdom resonates with us at all, why it registers as wisdom in the first place?

When I’m inspired by a single verse of Bible or Talmud or commentary, it’s usually because it crystallizes something that’s been building over a lifetime. What inspires is not the verse, but the universe behind it. Rainer Maria Rilke put it beautifully:

For the sake of a single verse, one must see many cities, men, and things. One must know the animals, one must feel how the birds fly and know the gesture with which the little flowers open in the morning. One must be able to think back to roads in unknown regions, to unexpected meetings and to partings one had long seen coming; to days of childhood that are still unexplained, to parents whom one had to hurt when they brought one some joy and did not grasp it (it was a joy for someone else); to childhood illnesses that so strangely begin with such a number of profound and grave transformations, to days in rooms withdrawn and quiet and to mornings by the sea, to the sea itself, to seas, to nights of travel that rushed along on high and flew with all the stars—and it is not yet enough if one may think of all this. One must have memories of many nights of love, none of which was like the others, of the screams of women in labor, and of light, white, sleeping women in childbed, closing again. But one must also have been beside the dying, must have sat beside the dead in the room with the open window and the fitful noises. And still it is not enough to have memories. One must be able to forget them when they are many, and one must have the great patience to wait until they come again.

Rilke was talking about writing, not reading. I think it applies just the same.

I’ll save my thoughts on where AI and VR/AR fit into this picture for a later post.

***

I wanted to share the following, which will be of interest to some of my readers.

Call for Abstracts: CCAR Journal Issue on AI and Judaism

How will the rise of artificial intelligence impact the future of Jewish thought, living, and practice? As we adopt new technological tools, how much is AI a difference of degree, and how much of kind? To explore these questions, we invite articles of 3000 to 4000 words for a future CCAR Journal issue focusing on how AI is changing the Jewish community. These topics may include (but are not limited to) the role of creativity, how AI has changed learning, questions of intellectual property, and the impact of AI on truth and falsity. As this field is rapidly changing, we encourage contributors to think in medium- and long-term timescales, informing how we can address the challenges we face in both the present and the future. We are interested in both philosophical and practical issues surrounding AI and Judaism, and both modern framing of ancient questions as well as unprecedented issues that have arisen. Please submit a 150-word abstract to geoff.mitelman@gmail.com and sarawolkenfeld@gmail.com by Tuesday, April 8.

Because of this trend, the most interesting stories to tell about positive religious engagement with technology usually revolve around information tech, and religious use of computers is no exception. Rabbis might not have known what to think about firearms—but they sure had opinions about the printing press!

Thanks to my friend and colleague Akiva Mattenson for helping me articulate this.

I'm a complete Duolingo addict (closing in on 1400 day streak). Gamifying something really works for me and probably for many people. I asked tech friends about making an app for my Yomi projects--Mishnah Yomit, Daf Shevui, but making it good, with games and points and competitions and leader boards, etc. Making it fun, not just read the Daf. They said it would be very expensive to set up and maintain. But I really think that like covering the pages of the book with honey for the little kids, adults need something like this. I think that Daf Yomi is already "gamified" but probably too hard of a game.

Thanks for your thoughts.

This is a great overview, David Zvi. I've also wondered for years why at least the Kabbalah Center people didn't try this in their (as you say, highly problematic) style.

My sense from some digital product experience is that we tend to underestimate how difficult and as Josh says, expensive it is to produce a truly compelling product in the way you outline. I think we'd need an applied visionary in Jewish education at the level of a Sarah Schenirer, Nechama Leibowitz or Rav Steinsaltz to do this well - with strong design abilities (rare) and of course engineering. (Maybe AI lowers the bar somewhat on those two now?)

The 929 Project is worth a mention here - it ticks some of your boxes and shows real innovation in this direction.